The Woven Heart of Japan: A Journey Through Its Flag Culture

Japan's streets are often adorned with a fascinating array of flags, a testament to a vibrant "flag culture" that continues to flourish even in today's rapidly developing media landscape. This steady progression is largely attributed to a gradual shift from mere functionality to a deeper role as repositories of emotional attachment. This journey through Japan's flags will explore their presence in six key aspects of daily life, history, and profound symbolism.

Flags of Daily Life

Summer in Japan can be quite challenging, especially after the rainy season, necessitating the constant carrying of handkerchiefs and umbrellas. To combat the intense heat, a small flag seen on the street can evoke a psychological sensation of coolness. This is the Ice Flag (氷旗 - kōri hata), a quintessential sign for Japanese ice cream shops. These flags typically share a similar design, having become an iconic symbol and a unique memory of summer. They feature a large red "ice" character on a white cloth background, often accompanied by traditional small bird motifs, all set against indigo sea wave patterns that are easily spotted from afar. In earlier times, much like childhood memories for some, ice was hand-shaved, with grandfathers topping the pristine ice shavings with sweet colored syrup and a tempting small cherry. While such traditional handmade shaved ice stalls are now rare, many snack shops and cafes proudly display ice flags at their entrances, signaling the availability of refreshing ice desserts inside.

Beyond the singular ice flags, banners are also commonly found in bustling shopping streets, a distinctly Japanese phenomenon where various shops converge. These streets are often covered, providing shelter from wind and rain, and are beloved places for leisurely strolls. To encourage consumption, merchants meticulously create a lively atmosphere with promotional flags hanging at storefronts and dazzling banners suspended overhead. These advertising flags are also rotated to reflect different seasons and events, such as New Year's, cherry blossom season, or Christmas.

Flags of History

In ancient Japan, flags served powerful functional roles. From the Heian period, for instance, Nobori Hata (幟旗) emerged during battles. Lacking telescopes and with warriors often dressed similarly, these flags solved the problem of misidentifying allies. A long, tall flag adorned with a family crest clearly indicated one's identity, allowing recognition even from a distance. From ancient times, Japanese flags came in diverse specifications – large and small, carried by hand or on the back, each with a specific function. Nobori Hata, originally military flags, are now frequently used for promotion and ceremonial events.

Flags also served as signals. Traditional Japanese wooden architecture posed a significant fire hazard, leading to devastating fires, particularly during the Edo period. Fire brigades employed various methods to alert people, including lanterns and flags. People stood in high places, waving flags to signal timely escape, much like the beacon fires along the Great Wall used as signal towers.

With the rapid economic development during the Meiji and Taisho eras, the demand for entertainment grew. Flags evolved from signifying identity to attracting and promoting, essentially becoming the equivalent of modern billboards. At that time, bustling areas like Shinjuku and Shibuya had not yet risen to prominence; instead, Asakusa was the favorite playground for Edo residents. Historical records show Asakusa streets teeming with theaters and colorful flags fluttering everywhere, creating a vibrant spectacle as people strolled with parasols and top hats, enjoying the fashionable life of the metropolis.

Flags of Youth

While the information age has introduced electronic advertising, reducing the number of traditional advertising flags, flags have certainly not disappeared. They remain a common sight in various school activities, particularly in sports competitions where the school flags (校旗 - kōki) of opposing teams are frequently displayed. Japanese university flags, in particular, are notably large. For example, during the annual Keio-Waseda match (慶早戦 - Keisō Sen), Waseda University's cheering squad has designated flag bearers responsible for wielding these massive banners. For these flag bearers, raising such a giant flag is no simple feat, demanding significant physical strength, necessitating the use of specialized waist protection devices for safety.

Not to be outdone by well-funded university teams, Japanese junior and senior high school students also enthusiastically embrace flags. Especially during sports festivals (taiiku-sai), flags are an excellent way for each class to express its spirit. These flags prioritize creativity, with students often DIYing their designs. The imagery is often imaginative, and even the flag shapes venture beyond the conventional. Students are frequently seen collaborating in school corridors, discussing their class flag designs. While the flag messages generally convey encouragement, the collaborative effort of children creating these flags is considered more meaningful than simply buying them. This process not only fosters class unity but also expresses genuine wishes, evoking a sense of the beauty of youth. Japanese children, through participating in club activities, are exposed to the competitive nature of sports early on. This is not solely for academic credit or physical fitness; Japanese sports exist for the sake of "winning". Consequently, flags displayed in competitive arenas begin to embody a sense of "honor".

Flags of Honor

Many Japanese anime feature a red flag emblazoned with "victory," which is distinct from a mere congratulatory banner. In Japanese culture, this is known as a Victory Flag (優勝旗 - yūshōki). Unlike the simpler flags with a pole and ordinary cloth encountered in daily life, Japanese victory flags are distinctly elaborate and expensive, demonstrating meticulous detail and luxurious materials.

Consider the well-known Koshien High School Baseball Tournament: the championship team not only receives a certificate of honor but, most importantly, is also awarded a victory flag. This flag is extraordinary, crafted entirely by hand by Japan's most skilled artisans. Its appearance alone conveys a sense of substantial weight and magnificence. Furthermore, when displayed individually, Japanese victory flags are not stood upright; they require a supporting stand to maintain an inclined angle, specifically designed to fully showcase the flag's patterns.

One might wonder about the strips of cloth hanging from the top of the victory flag. These are not arbitrary decorations; each strip represents the record of past winning schools. For a competition with a long history like Koshien, the appearance of this victory flag is incredibly inspiring. It is like a flying history book, chronicling the development of Japanese high school baseball from the Taisho and Showa eras through Heisei and Reiwa, continuously moving forward. The Koshien victory flag is formally returned by the previous year's winning team before the start of the tournament. After teams battle it out to determine the final victor, the victory flag is presented. Whether at Koshien or local community competitions, the awarding of the victory flag is always met with great solemnity and strict bowing gestures from both parties, signifying the importance of the event and respect for the opposing team. This highlights the Japanese emphasis on ritual and ceremony.

Flags of Wishes

Japanese flags exhibit a wide variety of shapes, including the beautiful and distinctive Carp Streamer (鯉魚旗 - koinobori). Pronounced koinobori, these flags have been used since the Edo period during the Boys' Festival (Tango no Sekku) to pray for the healthy growth of boys. Historical evidence for carp streamers can be found in Utagawa Hiroshige's famous ukiyo-e series, "One Hundred Famous Views of Edo". In addition to hanging carp streamers, the Boys' Festival also involves drinking iris sake and eating long, pointed rice dumplings, all for the purpose of praying for children's healthy development.

Carp streamers come in various materials, including cloth and paper, with colorful and elaborate patterns. Parents often write their children's names or wishes on them. They are particularly beautiful when set against a clear blue sky.

Another distinctive type of flag is the Offering Flag (奉納のぼり旗 - hōnō no nobori hata). Even in Japan's advanced modern society, Shinto and Buddhist cultures remain prevalent, with numerous shrines and temples found on city streets. Upon closer inspection, one will notice many long, narrow flags, typically in red and white, erected at their entrances. These are flags of offering, and the corners of each flag usually bear the information of the donor. In Japanese, these are called hōnō no nobori hata, akin to making a donation at a temple. For an ordinary shrine, the cost of one such flag is approximately 4,000 Japanese Yen, or less than 35 USD. Walking among these fluttering offering flags, one might imagine that people in the Edo period also practiced similar rituals, reflecting how, despite technological advancements like big data or artificial intelligence, humans still faithfully support the deities.

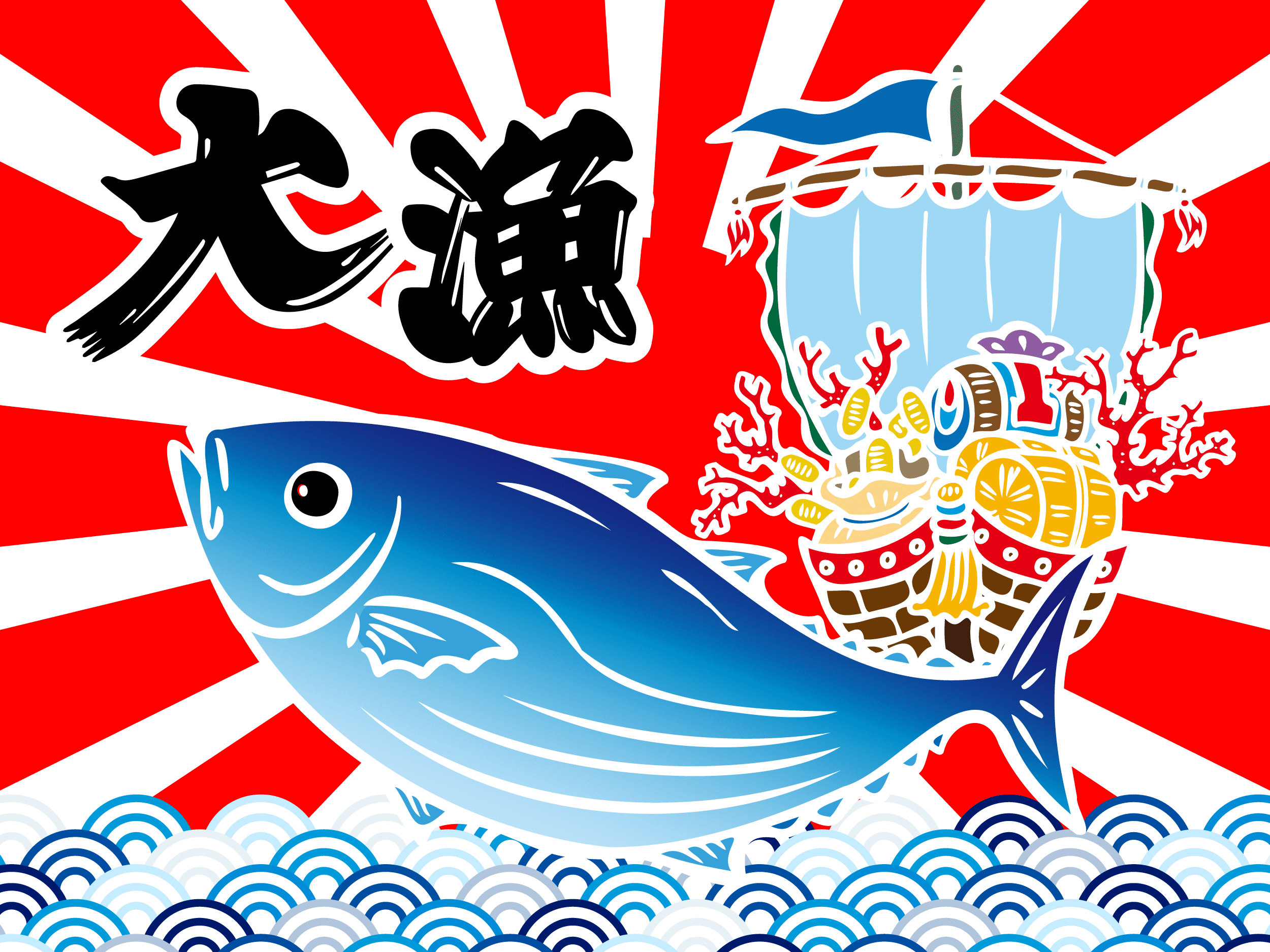

Beyond religious flags, another type of flag uniquely Japanese is the Big Catch Flag (大漁旗 - tairyōbata). Many Japanese restaurants decorate their walls with vibrant and colorful patterns often seen on Big Catch Flags to create an authentic izakaya atmosphere. This style, quite unlike the traditional subtlety of Japanese painting, is characterized by its striking and flamboyant depictions of waves and fish, clearly reflecting a grassroots aesthetic. As an island nation surrounded by the sea, fishing has a long and significant history for Japan. The origins of Big Catch Flags are debated: some say ancient ship owners awarded them to fishermen who caught large hauls, while others suggest they were used by some in the past to disguise military flags with bright colors to impersonate fishermen. Regardless of the true origin, Big Catch Flags have become a natural custom, much like hanging New Year pictures and couplets during Chinese New Year. People give Big Catch Flags as gifts to pray for abundant catches and safe voyages, with the flags embodying aspirations for good fortune. Due to their attractive and lively colors, Big Catch Flags are also used for decorative purposes.

Flags of Vitality

Japanese flags are intriguing because they can be both static and dynamic. There are many activities involving flag performances, one of which is a dance called Enbu (演舞), frequently seen in Japanese festivals, where flag dancing is a crucial component.

During one particular instance, passing by the entrance of Kyoto's Heian Jingu Shrine, one might stumble upon the grand Kyoto Student Festival. Without any prior knowledge of the event, simply joining the crowd for fun reveals the incredibly infectious energy of young people dancing and performing. Alongside numerous dance performances, there are dedicated flag dancers on stage, with an additional flag bearer positioned on the side below the stage. Observing a flag dancer nearby, the graceful and rhythmic way the flag unfurled and danced in their hands is truly difficult to describe without witnessing it firsthand. In that moment, the individual transformed from a typical student into a serene and valiant warrior, wielding a secret weapon whose next form was utterly unpredictable.

The Enduring Spirit of Japanese Flags

The range and "extensibility" of flags in Japanese culture are truly rich. Their sustained presence in modern society is largely due to their evolving role from mere functionality to an embodiment of added emotional value. Flags represent identity, and identity itself is a form of collectivism. Much like the Japanese affinity for cherry blossoms, which, though small, embody a powerful collective strength, flags serve a similar purpose. Humans, by nature, cannot remain detached when part of a collective. This intangible force of cohesion requires a physical manifestation, and thus, the "flag" is born. It can represent a class, a team, a company, or a nation.

Among ordinary people, the most powerful symbol of collective strength is often the national flag. Japan's national flag, called "Hinomaru" (日の丸), embodies their ancient reverence for the sun. The "white ground red circle" combination is a profound expression of the Yamato people's aesthetic sense. It is common to see large crowds holding small national flags bearing the Hinomaru design at events attended by the Japanese Imperial Family, enduring hours of sun and wind without complaint. Although the Imperial Family no longer holds political power and serves as a national symbol, this does not diminish the fervent support of ordinary Japanese citizens. This is the power of spiritual cohesion.

The Japanese national flag, a distillation of Japanese aesthetics, does not always appear in its literal form. It manifests in various ways, blurring its edges into an impression. Walking the streets of Kyoto and seeing a graceful geisha holding a red paper umbrella might spark a question: why does a red umbrella so often appear in Japanese culture? Does red represent strength? Does white represent the sun? Must the meaning of ancient objects be precisely defined, or is a blend of intuition and speculation more interesting, passed down through generations of devout belief? Similarly, while the Tokyo Skytree is Tokyo's tallest building, many retain a special fondness for its predecessor, Tokyo Tower. Beyond rational explanations, one might imagine the appearance of an unfurled red umbrella or the crimson hue amidst towering buildings – do they not bear a subtle resemblance to the "Hinomaru" of the Japanese national flag?

Ultimately, if flags possessed life, they would surely be weary. This soft, thin piece of white cloth is compelled to bear so much information imposed upon it: at one moment, a business card; at another, a promotional tool; sometimes dragged to a deep mountain temple, sometimes to a brutal battlefield. The information displayed on a flag can so easily stir the emotions of onlookers, a reality the flag itself surely never anticipated. The flag, inherently, is merely a medium, a tool, devoid of good or evil. Yet, its destiny is akin to gunpowder: in the hands of an artisan, it ignites a spectacular night sky; in the hands of a villain, it becomes a murder weapon. It is hoped that these flags will forever represent only goodwill, unity, and respect.

Related Articles

You may also like...

International Hostess Bar Since 1993

夢

ORIGIN

・ International Hostess Bar since 1993

・ Japanese Hospitality with International Service

・ Diverse and Charming Floor Ladies

・Located in Shinjuku, Tokyo

・Transparent Pricing

・Easy Online Reservations

.jpg)