Where Maturity Meets Indulgence

Ginza, often described as Tokyo’s “playground for adults,” is a district where elegance and extravagance coexist with the weight of history. For generations, “Ginza” has served as a metaphor for prosperity, inspiring other neighborhoods across Japan to adopt the name in hopes of mirroring its success. The area spans from Ginza 1-chome to 8-chome, with the 4-chome intersection at its heart—home to the iconic Wako Department Store, whose majestic white facade and clock tower mark one of the most recognizable intersections in Japan. When the Wako clock chimes, it’s said that time itself briefly pauses in Ginza.

The name "Ginza" (銀座) may trace back to a silver coin mint once located in the area. Following Tokugawa Ieyasu’s victory at Sekigahara in 1600, the mint was relocated to Edo in 1612. In the Edo period, however, Ginza bore little resemblance to its modern self—populated by artisans and marked by a slower, humbler pace than nearby Nihonbashi. Like most of Edo, it was built in wood—flexible in earthquakes but fatally vulnerable to fire.

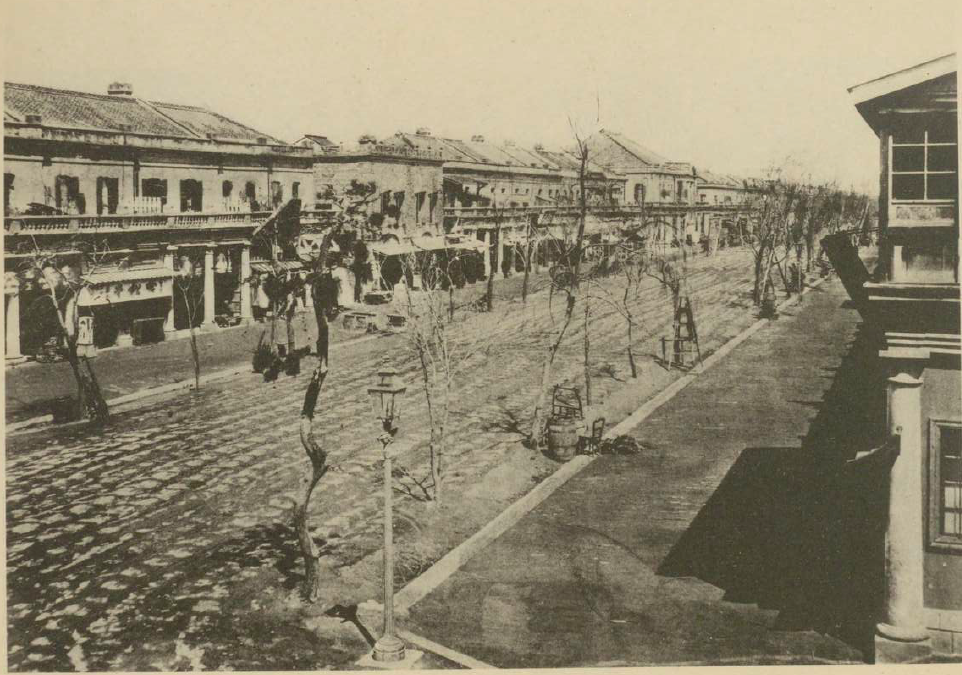

A City Reborn in Brick

In 1872, a massive fire razed Ginza, creating a blank slate just as the Meiji Restoration ushered in waves of Western influence. Though still clad in kimono, passersby began topping their outfits with bowler hats, embracing the visual paradox of Japan’s modernization. Governor Yuri Kosei and British architect Thomas James Waters led the reconstruction, envisioning a fireproof cityscape of red brick buildings. Thus emerged Ginza Brick Town, a gleaming district of gas-lit streets and Western architecture that dazzled the public.

.jpg)

But progress had a price. As Ginza’s land value soared, original artisan residents were priced out. In their place came Edo-period merchants flush with capital, who transformed the neighborhood into a commercial zone. Shops flourished, and Ginza began attracting high-end businesses, many of which still operate today. The Hattori Clock Shop became Ginza’s first clock tower in 1894—then would grow into the present-day Wako Department Store.

Disaster, Reconstruction, and the Birth of a Cultural Icon

The Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 devastated Tokyo and Yokohama, leveling Ginza and neighboring districts. The quake, registering a magnitude of 8.1, was so powerful it shifted the Great Buddha of Kamakura by nearly two feet. Over 100,000 people lost their lives. Libraries, universities, and cultural landmarks burned, including Ginza itself.

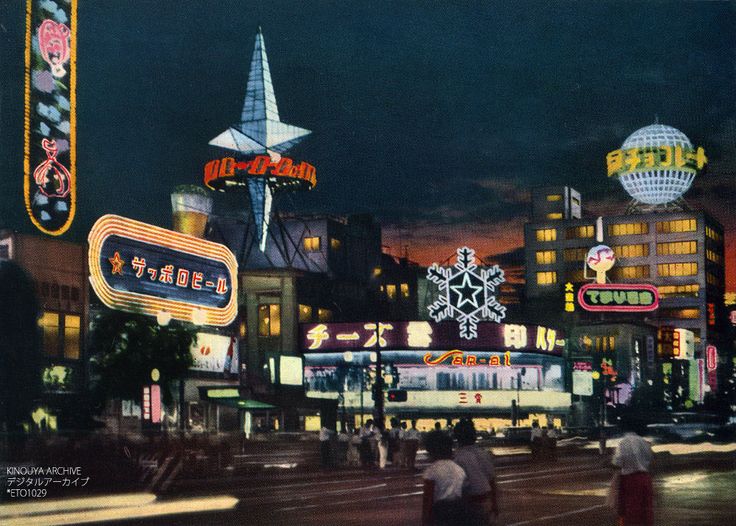

Yet the response was swift and determined. Just four years later, Japan opened Asia’s first underground rail: the Tokyo Metro Ginza Line, culminating in Ginza Station by 1934. Modern infrastructure ushered in a wave of affluence. Streets widened, shops multiplied, and the now-iconic Wako building—with its grand new clock tower—was completed. Ginza became synonymous with sophistication: women in kimonos sipped Western-style tea, crowds filled cafés, and rooftop photographers sought the perfect skyline shot. The city had risen from the rubble once again.

War, Occupation, and the Loss of Innocence

But history seldom allows uninterrupted peace. As Japan descended into militarism during the Showa era, Ginza’s glamour faded. Air raid drills replaced shopping sprees, and even children’s school supplies bore images of bombs and battleships. The attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 was followed by relentless U.S. air raids. In 1945, the iconic Wako Department Store fell under bombing fire.

After Japan’s surrender, Ginza came under the control of GHQ—General Headquarters of the Allied Powers. English signage sprouted, and American GIs filled the streets, some nicknaming it "Times Square." It was a surreal era, marked by cultural collision and subdued reconstruction.

And yet, Ginza endured.

Ginza in the Postwar Boom: Art, Ambition, and the Human Drama

As Japan embarked on its postwar economic miracle, Ginza transformed into the epicenter of ambition. The district became a competitive arena for adults—a place where wealth, taste, and desire collided. Cafés buzzed with the clink of teacups and the quiet murmur of dreams.

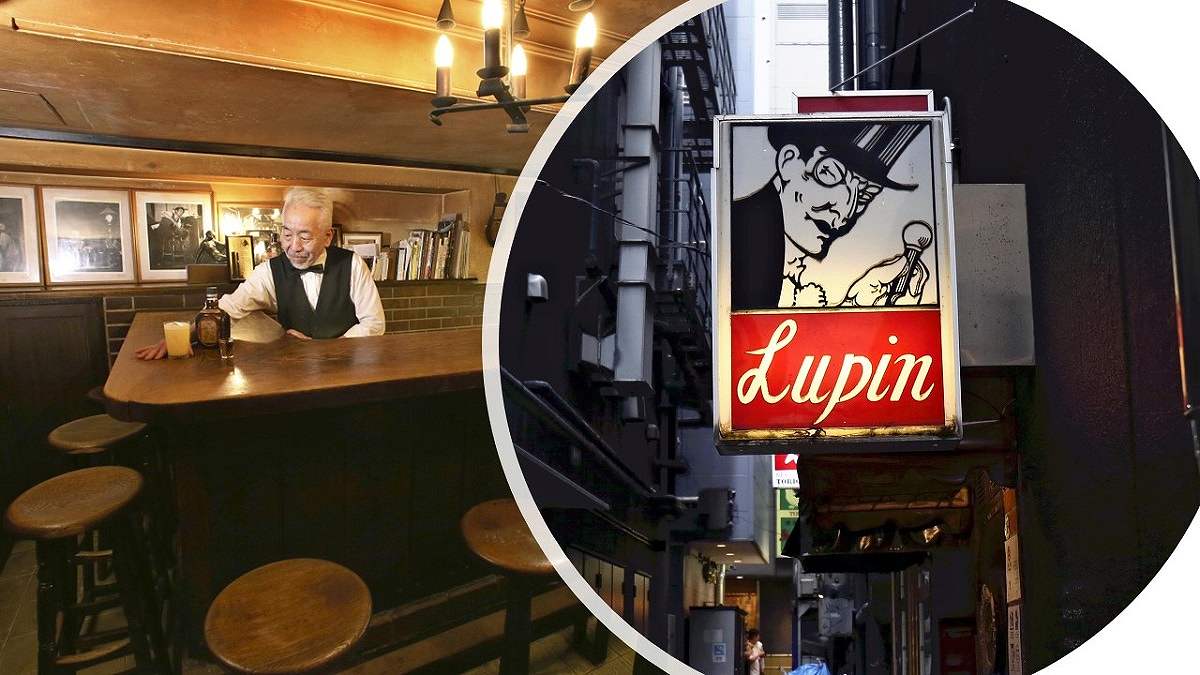

It was at Bar Lupin, a quiet Ginza café, that two legends of Japanese culture met: the androgynous singer Akihiro Miwa and the provocative writer Yukio Mishima. Their meeting was electric. Mishima, surrounded by admirers, commented that Miwa was “not cute,” to which Miwa coolly replied, “I’m beautiful—being cute is unnecessary.” The moment was immortal, the kind only Ginza could produce—a stage for Japan’s most brilliant minds and deepest contradictions.

Yet history haunted them both. The trauma of war, the fall of the Emperor, and American occupation gnawed at Mishima. In 1970, after a failed coup to restore imperial power, Mishima committed seppuku, ending his life in theatrical defiance. He had waited until Miwa’s final performance concluded before delivering a bouquet of roses and saying, “Thank you from the bottom of my heart.”

The Ginza of Today: Glamour, Pressure, and Ghosts of the Past

In times of peace, Ginza has become what it always aspired to be: a temple of fame and fortune. It is no longer the domain of barefoot artisans, but of global brands, haute couture, and sky-high real estate. Century-old businesses now compete with international luxury giants, and the once cohesive architectural style has given way to sleek, modern forms. Ginza is Japan’s most expensive district—and its most symbolic.

And yet, for all its glamour, Ginza risks becoming like any other upscale shopping destination. There are fast-fashion stores for the youth, luxury salons for the elite, and glittering showrooms for tourists. But true connection to a place goes beyond commerce. A city’s soul is not built from storefronts, but from stories, relationships, and shared memories.

The Echo That Never Fades

Ginza is more than a shopping street—it is a phoenix, reborn time and again from fire, earthquake, and war. Its clock tower, standing tall above Wako, continues to chime every hour—not just a signal of time, but a gentle echo of resilience. To walk through Ginza is to step through centuries of ambition, tragedy, art, and aspiration.

Ginza belongs to Tokyo. But the "Ginza dream"—the dream of rebuilding, of thriving, of rising above ruin—is a dream shared by every generation in Japan.

Related Articles

You may also like...

International Hostess Bar Since 1993

夢

ORIGIN

・ International Hostess Bar since 1993

・ Japanese Hospitality with International Service

・ Diverse and Charming Floor Ladies

・Located in Shinjuku, Tokyo

・Transparent Pricing

・Easy Online Reservations

.jpg)